Pine Island Glacier Births New ‘Berg

Downloads

- pineisland_oli_2017271_lrg.jpg (2142x1428, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: September 28, 2017

- Visualization Date: October 2, 2017

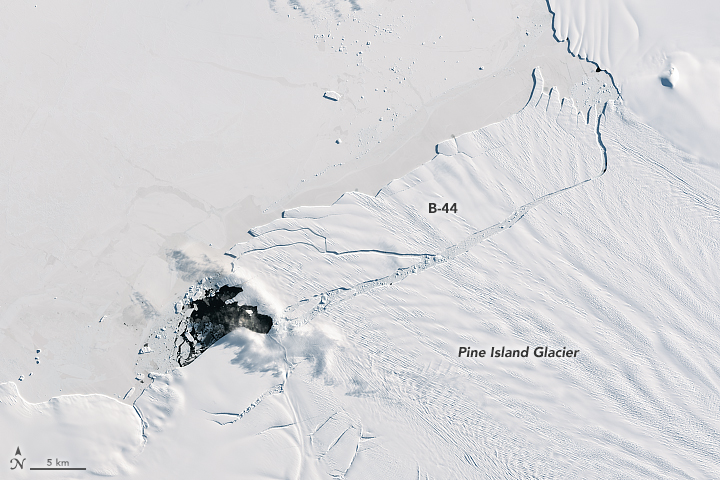

A new iceberg recently calved from Pine Island Glacier—one of the main outlets where ice from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet flows into the ocean.

On September 21, 2017, a rift was clearly visible across the center of the glacier’s floating ice shelf. The break ultimately produced iceberg B-44, visible in radar imagery captured on September 23 by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 satellite. On September 28, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 captured this natural-color image.

The new iceberg, afloat in the Amundsen Sea, has an area of about 185 square kilometers (72 square miles). That’s larger than the pieces that broke away in January 2017, but smaller than the 583-square-kilometer berg that broke loose in July 2015 and the 700-square-kilometer berg in November 2013.

Loss of ice from this glacier’s floating ice tongue is not new. Changes in the calving front have been well-documented in satellite imagery since at least 1973 (captured early that year with the Landsat Multispectral Scanner) and studied in detail. As the front of Pine Island retreats upstream, it has the potential to change the flow of the entire system. When ice is in contact with a neighboring ice shelf or the sides a fjord, it can buttress or hold back the ice behind it. If a glacier loses that connection through thinning, rifting, and retreat, inland ice can flow more freely.

According to NASA glaciologist Kelly Brunt, the September 2017 event may not immediately affect the flow of Pine Island Glacier because the ice that calved was already disconnected from much of the system. “This iceberg was the last bit of ice to calve off that was not ‘holding on’ to the sides of the embayment,” Brunt said.

Now that B-44 has calved, all of the ice remaining in Pine Island Glacier appears well connected to its margins. The huge stresses along the glacier’s sides—the so-called “shear margins”—are evident in the series of rifts and crevasses along the glacier’s edges and on the iceberg. “If another event happens fairly soon, that could have a more measurable impact on the flow of the system,” Brunt said.

Fractures elsewhere on the ice also affect the glacier, according to NASA glaciologist Chris Shuman. The rift that ultimately produced B-44 opened from the glacier’s center before propagating out to the margins. Fractures spanning the glacier have weakened the ice, evident in recently calved bergs in 2015 in 2017 that were almost immediately torn apart by winds and currents.

References and Related Reading

- Jeong, S. et al. (2016) Accelerated ice shelf rifting and retreat at Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters, 43 (22), 11,720-11,725.

- MacGregor, J. A. et al. (2012) Widespread rifting and retreat of ice-shelf margins in the eastern Amundsen Sea Embayment between 1972 and 2011. Journal of Glaciology, 58 (209), 458-466.

- U.S. National Ice Center (2017, September 25) Iceberg B-44 Calves off Pine Island Glacier into the Amundsen Sea. Accessed September 26, 2017.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.