Automating the Detection of Landslides

Downloads

- jure_oli_2014261.jpg (720x533, JPEG)

- jure_oli_2013258_lrg.jpg (1200x1200, JPEG)

- jure_oli_2013258_geo.tif (1200x1200, GeoTIFF)

- jure_oli_2014261_lrg.jpg (1200x1200, JPEG)

- jure_oli_2014261_geo.tif (1200x1200, GeoTIFF)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: September 18, 2014

- Visualization Date: July 6, 2016

As farmers in Nepal prepare for the benefits of monsoon season, Dalia Kirschbaum anticipates the dangers of those torrential rains—mainly, the loosening of earth on steep slopes that can lead to landslides. In this mountainous country, 60 to 80 percent of the annual precipitation falls during the monsoon (roughly June to August). That’s when roughly 90 percent of Nepal’s landslide fatalities also occur, according to a 2015 report from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

“We know a high number of landslides occur around this time, so documenting them is really important, especially to better characterize when these events happen and what impact they have,” said Kirschbaum, a landslide expert at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Kirschbaum oversees a team of researchers designing an automated system to identify potential landslides that might otherwise go undetected and unreported. The computer program scans satellite imagery for signs that a landslide may have occurred recently.

The Sudden Landslide Identification Product (SLIP) combs through Earth imagery and analyzes consecutive images of the same location to spot changes in soil moisture, muddiness, and other surface features. The program also compares the hill slopes with topographic information derived from digital elevation models, such as those built from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) and the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emissions and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER). By combining this information, SLIP can automatically pinpoint the locations of possible landslides each time a new, cloud-free land image is acquired.

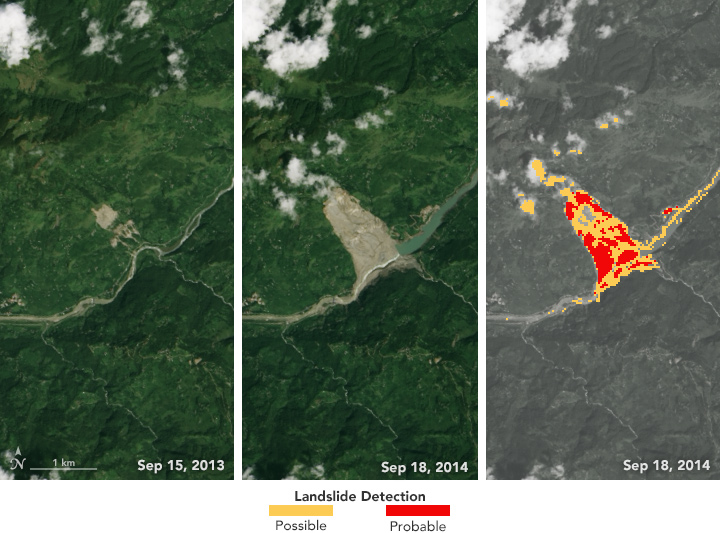

The left and middle images above were acquired by the Landsat 8 satellite on September 15, 2013, and September 18, 2014—before and after the Jure landslide in Nepal on August 2, 2014. The image on the right shows that 2014 Landsat image processed with the new SLIP algorithm. The red areas show most of the traits of a landslide, while yellow areas exhibit a few of the proxy traits.

What the Goddard team cannot determine from images alone is when a landslide occurred. Landsat, for instance, takes 16 days before it passes over the same spot on Earth. To more precisely pin a date on each landslide, Kirschbaum and colleagues turn to rainfall measurements from the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission. The GPM core satellite measures rain and snow several times daily, allowing researchers to create maps of rain accumulation over 24-, 48-, and 72-hour periods for given areas of interest—a product they call Detecting Real-time Increased Precipitation, or DRIP. When a certain amount of rain has fallen in a region, an email can be sent to emergency responders and other interested parties.

“We’re interested in rapidly and precisely identifying unreported landslides to better understand landslide triggering conditions,“ said Aakash Ahamed, who worked on the project at Goddard as part of the NASA DEVELOP program. “This information can improve maps that show which areas are susceptible to landslides, and it can promote responsible management.”

Though still in the testing phase, the SLIP-DRIP software is open source and available to the public. Ahamed, Kirschbaum, and colleagues believe it could significantly improve landslide inventories, leading to better risk management. This information will ultimately be fed into NASA’s Global Landslide Catalog—the first and only global database of rainfall-triggered landslides. The catalog is accessible to emergency response teams, researchers, and the public. To date, the catalog has only included landslides reported in news outlets, online journals, and disaster databases. SLIP-DRIP products will make that information more current and comprehensive.

“While the Global Landslide Catalog has already provided some really interesting insight into where and when landslides are occurring, being able to capture information from satellite-based sources provides a more robust way of figuring out the true frequency and impact landslides can have,” said Kirschbaum.

Related Reading

- NASA Applied Sciences (2016) DEVELOP National Program. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- NASA Applied Sciences (2016) DEVELOP DRIP and SLIP Landslide Detection Package. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- NASA (2016) Global Landslide Catalog. Accessed July 7, 2016.

- ICIMOD (2016) Consultative Workshop—Landslide Inventory, Risk Assessment, and Mitigation in Nepal. Accessed July 7, 2016.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Landslide detection data courtesy of Jessica Fayne. Aakash Ahamed, Amanda Rumsey, and Justin Roberts-Pierel (USRA) contributed to this research. Caption by Kasha Patel, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, with Mike Carlowicz.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.