The Sinuous Shenandoah

Downloads

- shenandoah_oli_2013294_lrg.jpg (6000x4000, JPEG)

- wideshenandoah_oli_2013294.jpg (720x720, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: August 3, 2013

- Visualization Date: December 4, 2014

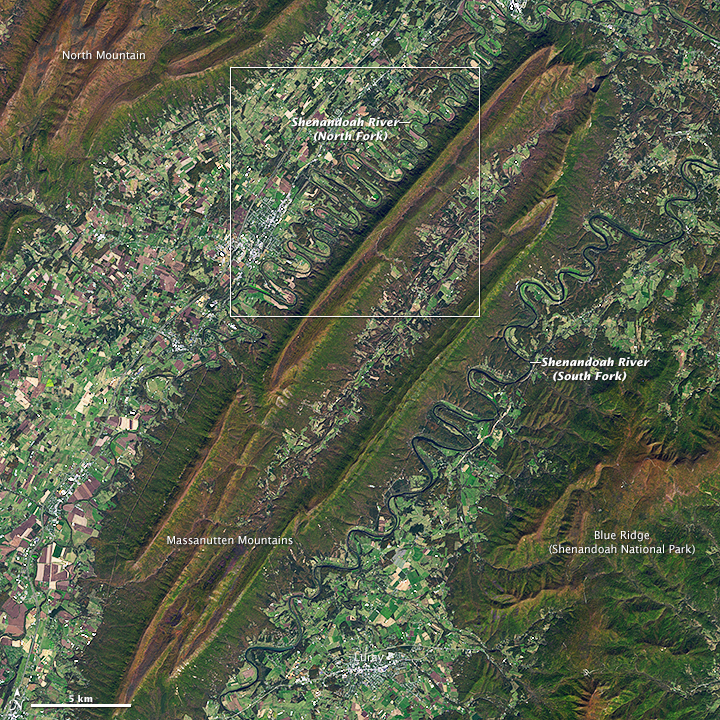

Meandering rivers are so commonplace that they are easy to ignore. But if you happen to fly over the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, you might catch a glimpse of a stretch of river that you won’t soon forget.

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured this view of the meanders on August 3, 2013. The top image shows a detailed view of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River near Woodstock, Virginia, where the river’s meanders are unusually sharp and tightly packed. In 48 miles (77 kilometers) of flow, the river travels only 16 miles (26 kilometers) as the crow flies. The lower image offers a broader view of the area. While the river’s winding pattern is most pronounced between Strasburg and Edinburg, the South Fork of the Shenandoah also takes a remarkably sinuous path as it flows toward Front Royal, Virginia.

How did the Shenandoah River get such a distinctive shape in this area? According to geologist Callan Bentley of Northern Virginia Community College, the modern landscape was sculpted by a series of geological processes spanning hundreds of millions of years.

The story begins some 500 million years ago during the Cambrian Period, when layers of sandstone, shale, and limestone were being built along the edge of an ancient predecessor of the continent we now call North America. The gradual deposition process that created the sedimentary rocks went on for 200 million years—a period about 1,000 times longer than modern Homo sapiens have existed as a species.

About 300 million years ago, Africa began a cataclysmic, slow-motion collision with North America that thrust those sandstone, shale, and limestone layers—which had been horizontal when they formed—into a complex mash of northeast-southwest trending folds and rugged mountain ridges. Geologists call this period of mountain-building the Alleghanian orogeny.

As the pressure forced mountain ridges up, rock layers were pressed so intensely that they cracked in many places. Hundreds of northwest-southeast fractures emerged perpendicular to the rising mountain ridges. As hundreds of millions of years passed, the rugged mountains that rose during the Alleghanian orogeny were eroded away by wind and water until the area was nearly flat once again.

Rivers need relatively gentle landscapes to meander, and it was in this period—sometime in the past 100 million years—that the Shenandoah River probably began to assume its modern meandering form. Rather than forming irregular meanders as most rivers do, the Shenandoah followed that pre-existing network of fractures in the bedrock formed during the Alleghanian orogeny. “The water simply found it easier to follow those fractures than to cut down into unfractured bedrock, particularly in the shale and clay-rich sandstone northwest of the Massanutten mountain system,” explained Bentley.

While the same processes occurred on the South Fork, the meanders are less pronounced, perhaps because there are fewer fractures on that side of the ridge. “Later on, when the modern Appalachian Mountains were uplifted or the river’s base level dropped—or both—the river began to cut down anew, and the meanders we see today became ‘locked in place’ along the fracture set,” Bentley said.

References and Further Reading

- Bentley, C. The Alleghanian Orogeny. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Bentley, C. Geology of Virginia 2014. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- College of William & Mary The Potomac-Shenandoah System. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Hack, J.T. & Young, R.S. (1959) Intrenched [sic] meanders of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, Virginia. USGS Professional Paper, 1-10.

- Bentley, C. via Mountain Beltway (2011, October 25) Meanders of the south fork of the Shenandoah River. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2014, December 3) Meandering in the Amazon.

- Sierra Potomac Meandering Rivers. Accessed December 1, 2014.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michael Taylor and Adam Voiland, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Adam Voiland.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.