Retreat of Alaska’s Columbia Glacier

Downloads

- 19860728_lrg.jpg (1920x1080, JPEG)

- columbia_tm5_2011120_lrg.jpg (1920x1080, JPEG)

- columbia_glacier.kml (KML)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 5 - TM

- Data Date: July 28, 1986 - May 30, 2011

- Visualization Date: May 16, 2012

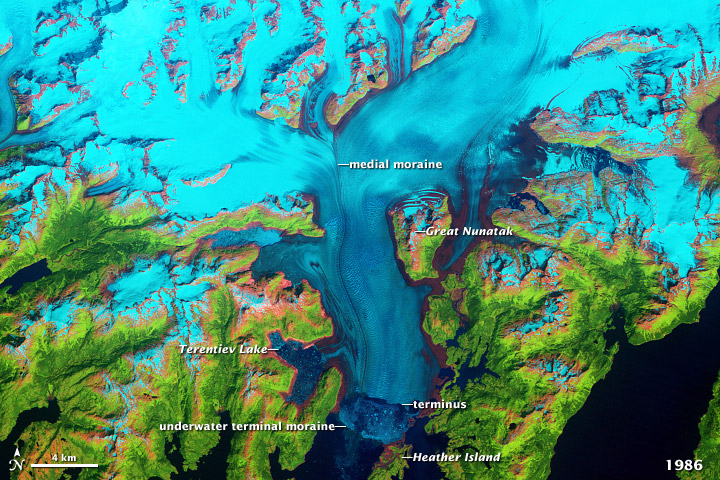

The Columbia Glacier descends from an ice field 3,050 meters (10,000 feet) above sea level, down the flanks of the Chugach Mountains, and into a narrow inlet that leads into Prince William Sound in southeastern Alaska. It is one of the most rapidly changing glaciers in the world.

The Columbia is a large tidewater glacier, flowing directly into the sea. When British explorers first surveyed it in 1794, its nose—or terminus—extended south to the northern edge of Heather Island, a small island near the mouth of Columbia Bay. The glacier held that position until 1980, when it began a rapid retreat that continues today.

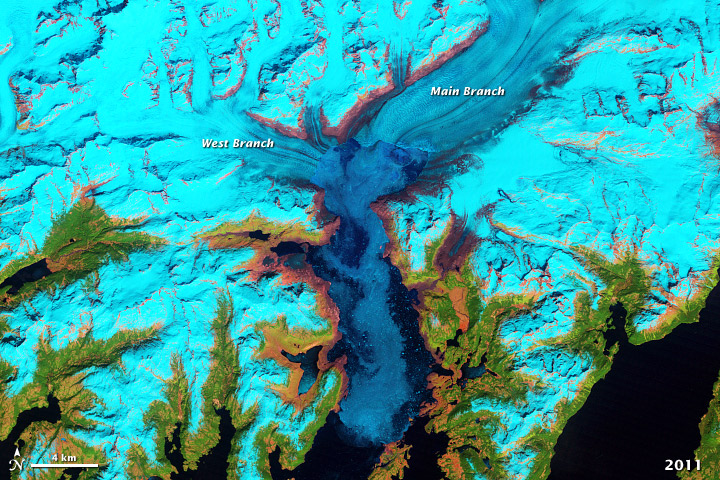

These two false-color images, both captured by the Thematic Mapper (TM) instrument on Landsat 5, show the glacier and the surrounding landscape in 1986 and 2011. Snow and ice appears bright cyan, vegetation is green, clouds are white or light orange, and the open ocean is dark blue. Exposed bedrock is brown, while rocky debris on the glacier’s surface is gray. The 2011 image has more snow because it was captured in May, while the 1986 image was captured in July.

In 1986, the glacier's terminus was just a few kilometers north of Heather Island. By 2011, it had retreated more than 20 kilometers (12 miles) to the north, moving past Terentiev Lake and Great Nunatak Peak. As the glacier has retreated, it has also thinned substantially, as shown by the expansion of brown bedrock areas. Rings of freshly exposed rock, known as trimlines, are prominent in the later image. Since the 1980s, the glacier has lost about half of its total thickness and volume.

Like bulldozers, glaciers lift, carry, and deposit sediment, rock, and other debris from Earth’s surface. This mass accumulates on leading edges in piles called moraines. Columbia Glacier’s terminal moraine forms a shallow underwater ridge that, as shown in the 2011 image, prevents icy debris and icebergs from drifting past it.

The retreat has also changed the way the glacier flows. The medial moraine, a line of debris deposited when separate channels of ice merge (seen here as a line in the center of the 1986 image) served as a dividing line between the Main Branch and West Branch of the glacier. By 2011, the retreating terminus had essentially split the Columbia into two glaciers, causing calving to occur on two fronts.

Read more about the Columbia Glacier in our World of Change section.

References

- Krimmel, R. (2001) Photogrammetric Data Set, 1957-2000, and Bathymetric Measurements for Columbia Glacier, Alaska. U.S. Geological Survey.

- McNabb, R.W. (in press). Using Surface Velocities to Calculate Ice Thickness and Bed Topography: A Case Study at Columbia Glacier, Alaska. Journal of Glaciology.

- Rasmussen, L.A. (2011, January 17). Surface Mass Balance, Thinning, and Iceberg Production, Columbia Glacier, Alaska, 1948-2007. Journal of Glaciology.

- O'Neel, Shad. (2012) Surface Mass Balance of the Columbia Glacier, Alaska, 1978 and 2010 Balance Years. (pdf) U.S. Geological Survey Data Series.

- O'Neel, Shad. (2005, September 20) Evolving Force Balance at Columbia Glacier, Alaska, During Its Rapid Retreat. Journal of Geophysical Research.

- Post, A. (2011, September 13) A Complex Relationship Between Calving Glaciers and Climate. EOS.

- Walter, Fabien. (2010, August 7). Iceberg Calving During Transition from Grounded to Floating Ice: Columbia Glacier, Alaska. Geophysical Research Letters.

NASA images by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using Landsat 5 data from the USGS Global Visualization Viewer. Caption by Adam Voiland, with information from Shad O'Neel and Robert McNabb.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.