Intense, Widespread Drought Grips South America

Downloads

- solimoesriver_oli_20210921_lrg.jpg (1783x1857, JPEG)

- solimoesriver_oli2_20240921_lrg.jpg (1783x1857, JPEG)

- sadrought_grc_20241007_lrg.jpg (3695x4362, JPEG)

- safires_epc_20240903_lrg.jpg (1705x1705, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Landsat 9 - OLI-2

- DSCOVR - EPIC

- Data Date: September 21, 2021 - September 21, 2024

- Visualization Date: October 10, 2024

Rivers in the Amazon basin fell to record-low levels in October 2024 as drought gripped vast areas of South America. Months of diminished rains have amplified fires, parched crops, disrupted transportation networks, and interrupted hydroelectric power generation in parts of Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela.

This pair of Landsat images illustrates the shrinking Solimões River near Tabatinga, a Brazilian city in western Amazonas near the border with Peru and Colombia. The image above (right) was captured by the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on September 21, 2024. The other image (left) shows the same area on September 21, 2021, when water levels were closer to normal.

On October 4, 2024, river gauge data from the Brazilian Geologic Service indicated that the Solimões had fallen to 254 centimeters below the gauge’s zero mark, a record low. Rivers that day also reached record lows near the cities of Porto Vehlo, Jirau-Justante, Fonte Boa, Itapéua, Manacapuru, Rio Acre, Beruri, and Humaitá. Water height data collected by satellite altimeters and processed by a team of NASA scientists reported unusually low water levels at several Brazilian lakes and reservoirs as well, including Lake Tefe, Lake Mamia, Lake Mamori, Lake Ariau, Lake Faro, and Lake Erepecu.

The drought is related in part to the lingering impact of El Niño, a climate pattern that was present for the latter half of 2023 and first half of 2024. The phenomenon—associated with an unusually warm layer of water in the equatorial Pacific—typically shifts rainfall patterns in a way that reduces rain in the Amazon, especially during the dry season months of July, August, and September, according to Prakrut Kansara, a hydrologist at Johns Hopkins University.

Brazil’s National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters (CEMADEN) noted that an area of unusual warmth in the North Atlantic may have also affected rainfall patterns and contributed to the drought. “The magnitude of the current drought is roughly double what the region saw in 2015-2016, the last time a strong El Niño occurred,” Kansara said.

Kansara is part of a USAID-NASA SERVIR project that provides retrospective analyses of the region’s hydrometeorology and produces fire risk forecasts for CEMADEN. The team’s analysis indicated that western Amazonas in Brazil, northern Peru, eastern Colombia, and southern Venezuela received more than 160 millimeters (6 inches)—less rain in July, August, and September than usual. During that period, streamflow dropped more than fourfold, according to Kansara.

Since early 2024, the team’s seasonal forecasts warned that the Amazon basin would face extreme fire conditions during the dry season. Indeed, expansive plumes of smoke enveloped the southern Amazon between July and October, particularly in the Pantanal region that spans parts of southern Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia. Data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research and the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service shows that the Pantanal region—and especially Bolivia—has experienced one of its worst fire seasons in decades. NASA’s EPIC (Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera) imager on the DSCOVR (Deep Space Climate Observatory) satellite captured the image of smoke billowing from the fires in the Pantanal shown below on September 3, 2024.

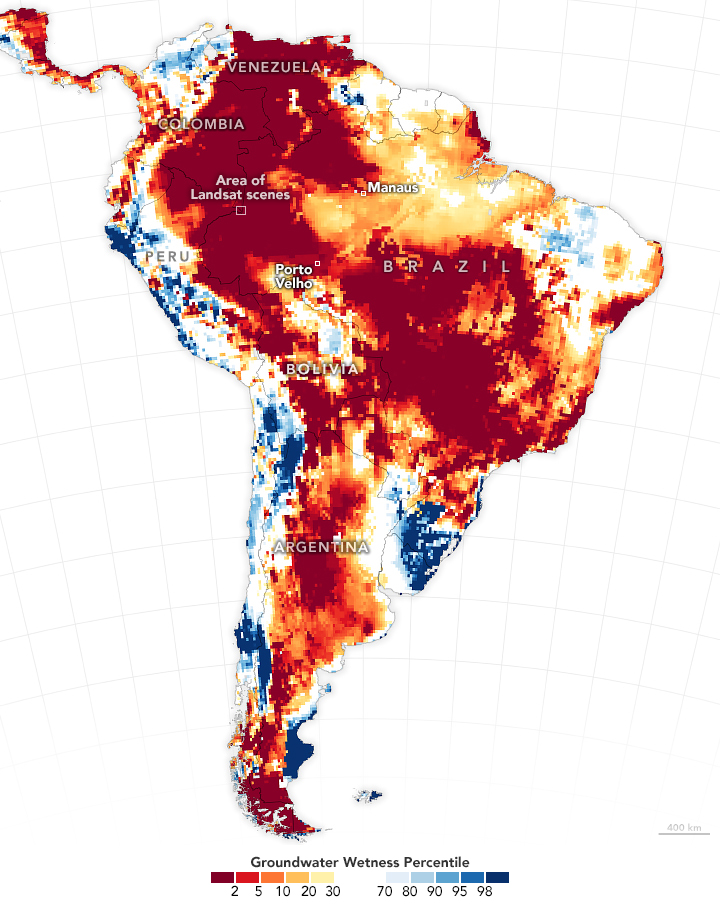

Lack of rainfall, low soil moisture, and a drawdown of groundwater helped amplify the fires and caused them to spread faster and farther. The map above shows shallow groundwater storage for the week of October 7, 2024, as measured by the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment Follow-On (GRACE-FO) satellites. The colors depict the wetness percentile, or how the amount of shallow groundwater compares to long-term records (1948-2010). Blue areas have more water than usual, and orange and red areas have less.

“Low rainfall in the Pantanal during last year's wet season—roughly November through February—predisposed this region to a greater risk of fire,” said Doug Morton, an Earth system scientist based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “On the GRACE map, you also see a strong drought signal to the north in Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, and western Brazil—the source of many of the rivers that are now running dry across the central Amazon.”

Drought impacts have been far-reaching. News reports indicate that the drought has strained power supplies in Brazil and Ecuador as hydroelectric power stations generate less electricity. Snarled transportation networks and impassable rivers have left some communities struggling to get supplies, according to Reuters.

The drought is also affecting scientific research. “We work with colleagues in Peru, Brazil, and Ecuador on an early warning forecast system for malaria who haven’t been able to access some research sites due to low water levels,” said Kansara.

CEMADEN called the current drought the most intense and widespread Brazil has experienced. A drought update published on October 3 indicated that the number of Brazilian municipalities facing extreme drought was poised to increase from 216 in September to 293 by the end of October.

References

- Associated Press (2024, September 12) Severe drought drops water level to historic low on the Paraguay River, a regional lifeline. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- The City Paper (2024, October 2) Amazon drought hits indigenous communities of Leticia and Puerto Nariño. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- CNN (2024, September 30) Stark before-and-after pictures reveal dramatic shrinking of major Amazon rivers. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- Copernicus (2024, September 23) Copernicus: Pantanal and Amazon wildfires saw their worst wildfires in almost two decades. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- Feron, S. et al. (2024) South America is becoming warmer, drier, and more flammable. Communications Earth & Environment, 5(501).

- France24 (2024, September 19) Amazon drought leaves Colombian border town high and dry. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- Geopolitical Futres (2024, September 20) Ecuador’s Power Crisis. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2024, September 7) Smoke Fills South American Skies. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2022, February 3) A Human Fingerprint on the Pantanal Inferno. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- National Center for Monitoring and Alerts for Natural Disasters (2024, October 3) Number of municipalities in extreme drought situation expected to rise 35.64% in October. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- National Center for Monitoring and Alerts for Natural Disasters (2024, October 2) Monitoring drought and its impacts in Brazil. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- Reuters (2024, October 2) Extreme drought isolates Amazon communities in Brazil. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- Reuters (2024, October 4) Brazil drought drops Amazon port river level to 122-year low. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- SACE (2024) Bacias Monitoradas. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- Santos de Lima, L. et al. (2024) Severe droughts reduce river navigability and isolate communities in the Brazilian Amazon. Communications Earth & Environment, 5(370).

- SERVIR (2024) Amazon Fire Dashboard. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- SGB (2024) 38° Boletim Hidrologico da Bacia do Amazonas. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- The Washington Post (2024, September 12) More than half of Brazil is racked by drought. Blame deforestation. Accessed October 10, 2024.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, GRACE-FO data (NASA-GFZ) available from the National Drought Mitigation Center, and DSCOVR EPIC from NASA. The fire risk forecasts and hydrometeorological analyses from the USAID-NASA SERVIR project use data from NASA’s GEOS S2S forecast model, the Land Information System (LIS), and Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG). Story by Adam Voiland.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.