NASA Returns to the Beach: Wide Wildwood Beaches

Downloads

- wildwood_tm5_1986207_lrg.jpg (1883x949, JPEG)

- wildwood_oli_2019201_lrg.jpg (1883x949, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: July 26, 1986 - July 20, 2019

- Visualization Date: June 27, 2024

Since publishing NASA Earth Observatory Goes to the Beach in July 2017, we have explored even more of the planet’s coasts via satellite images and astronaut photographs. This week, we return to the beach with a look back at some of our favorite seaside stories published in recent years. The images and text on this page first appeared on August 5, 2019.

To get from the boardwalk or street to the surf in Wildwood, you have to walk the length of four to six football fields. For many people, there is great joy and good summer business to be found on the widest beach in New Jersey and one of the widest on any coast. For others, the vast strip of sand is a deterrent and problem.

Along the 130-mile (210-kilometer) New Jersey shoreline, most of the beaches and barrier islands are retreating due to a combination of natural geologic processes, commercial and residential development, and sea level rise. The state and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers work annually to shore up and replenish those beaches.

But not in Wildwood. For more than a hundred years the beaches have been growing wider. The mayor once told WHYY radio: “We’re so popular, even the sand wants to come here.”

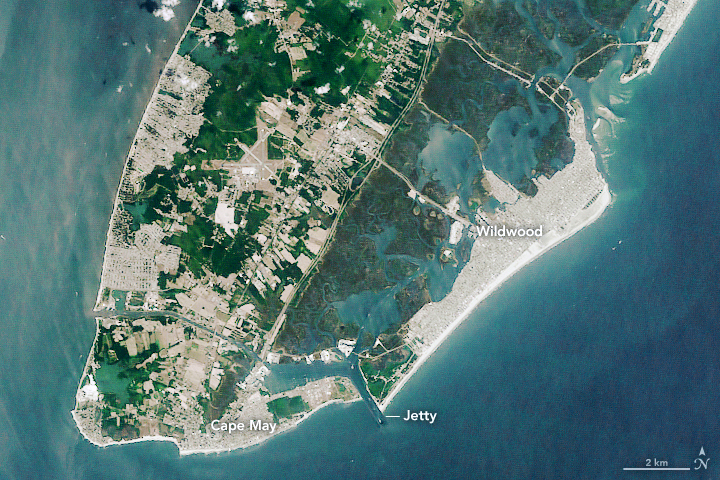

The images above, captured by Landsat satellites, show 33 years of shoreline change at the southern tip of New Jersey. The first (left) image was acquired by Landsat 5 on July 26, 1986; the second image shows the same area on July 20, 2019. The changes in color are due to variations in the satellite imagers and in the light reflecting off the land and water. However, vegetation cover also appears to have changed over the years.

Sand naturally moves south-southwest along this stretch of the coast due to processes such as longshore drift. Evidence of this appears in the changing of the spit northeast of Hereford Inlet; in the retreating shore of North Wildwood; and in the widening beach in Wildwood and near the jetty. In recent years, coastal managers have moved millions of tons of sand each spring from Wildwood to North Wildwood—they call it “backpassing”—to offset what nature takes away.

Nature is not the only reason for the widening of Wildwood’s beach. From 1903 to 1911, dredges dug up a tidal marsh and carved out 500 acres of harbor behind Cape May, one of America’s oldest coastal playgrounds. Then engineers built a jetty to protect the inlet; it reaches 4,500 feet (1,400 meters) into the Atlantic Ocean. About a decade later, developers working in Wildwood built a causeway across Turtle Gut Inlet, restricting natural tidal flow to a point where the inlet filled in and eventually became another source of sand for the beach.

With both projects, humans changed the natural movement of sand along the shore, building up Wildwood and starving Cape May of replenishing sand. Humans have had to take over the job that nature once did. Since the 1990s, workers have pumped more than 12 million cubic yards of sand back up onto the Cape’s beaches.

Back in Wildwood, the beaches keep growing and the town keeps making the most of it. The area hosts some of the largest kite and frisbee festivals in the country, and more than 20,000 to 30,000 people have attended country music concerts on the sand in the past decade.

The vast stretch of sand is less appealing to the elderly and people with wheelchairs and other mobility challenges. Another concern is occasional flooding. Because the sand stands several feet higher than the storm drains in some parts of town, temporary ponds can form in the midst of the beach.

Though an idea to shuttle people to the water line via camel was nixed by the town years ago, some people ease the trip by summoning an all-terrain beach taxi or by using a sled to drag their beach gear. Most just enjoy the extremely walkable sand and the fantastic body surfing in the water.

References

- E&E News via Scientific American magazine (2019, March 26) Coastal Conservation Plan Sparks Fight Over Sand. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- Philadelphia magazine (2016, October 8) Why’s Everyone Freaked Out About Cape May Beach? Accessed August 1, 2019.

- The Press of Atlantic City (2018, April 9) New Jersey shore sees sea level change—and it can't be denied. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- The Press of Atlantic City (2018, March 5) Bulkhead saves North Wildwood from disaster beyond beach erosion. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- Stockton University (2019) Coastal Research Center. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- WHYY (2019, April 25) Annual Wildwoods sand transfer underway. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- WHYY (2019, February 1) Why engineers use different barriers to protect NJ coastal towns. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- WHYY (2016, November 11) Why Wildwood’s beaches are so big. Accessed August 1, 2019.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Michael Carlowicz, with image interpretation from Stewart Farrell, Stockton University.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.