Malta’s Landscape of Limestone

Downloads

- malta_oli2_2022300_lrg.jpg (4720x4720, JPEG)

- malta_oli2_2022300.jpg (720x480, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 9 - OLI-2

- Data Date: October 27, 2022

- Visualization Date: December 16, 2022

Today’s story is the answer to the December 2022 puzzler.

Malta, the archipelago located between the Italian island of Sicily and the North African coast, grew from materials that were once at the bottom of the sea. Millions of years later, those materials would form the bedrock of the region’s built environment.

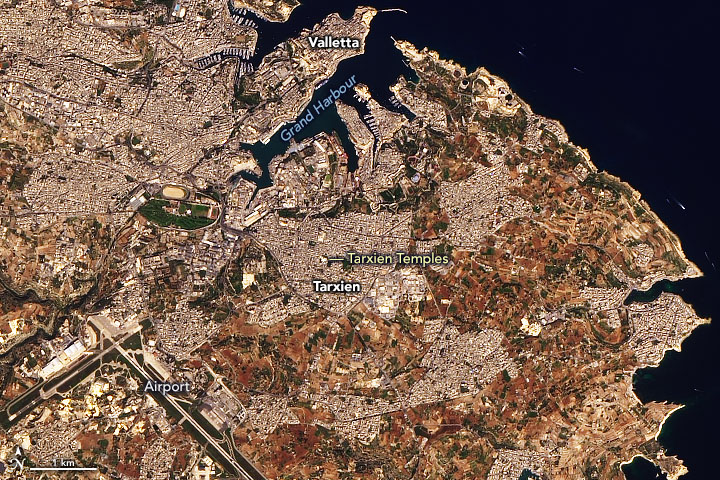

The Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on Landsat 9 acquired these natural-color images of the archipelago on October 27, 2022. Most prominent in the image above are the island nation’s three largest islands: Malta, Gozo, and Comino.

Notice the yellow-gray hue across much of the islands, especially at built-up areas and beaches. This is the color of limestone—a major geologic component of the island and a widely used building material. The oldest rocks are lower coralline limestone, which formed as the skeletons of coral and other aquatic creatures built up from at the seafloor starting around 30 million years ago. The second-oldest rocks are globigerina limestone, which formed from the calcium carbonate shells of marine plankton. Outcrops of these rocks span about 70 percent of the islands.

In Valletta, the island nation’s capital city, fortifications were built using limestone excavated from surrounding ditches. The walled city—built after the Siege of Malta in 1565—is located on a peninsula between two harbors, which has helped the perimeter of this UNESCO world heritage site to remain mostly unchanged.

There are places where use of the islands’ limestone for building dates even farther back. Several megalithic temples across the islands were built during the fourth and third millennium B.C.E. and are among the oldest-known freestanding structures on Earth. Island inhabitants often used the harder coralline limestone for external walls and the softer globigerina limestone for interior spaces and decoration.

Although the structures have stood for millennia, they remain susceptible to degradation from the surrounding environment. The detailed image shows the area around the prehistoric complex of Tarxien. Notice the white tent, which was erected over the complex to help shelter it from the weathering effects of rain and sunlight. Experts continue to monitor how these and other factors, such as salt, humidity, and temperature fluctuations, affect the structures.

References

- Cassar, J. et al. (2018) Sheltering archaeological sites in Malta: lessons learnt. Heritage Science, 6, 36.

- Environment & Resources Authority Maltese Geology. Accessed December 19, 2022.

- GuideMeMalta Limestone country: the story behind Malta’s iconic golden hue. Accessed December 19, 2022.

- Heritage Malta (2022) Tarxien Prehistoric Complex. Accessed December 19, 2022.

- The New York Times (2016, November 2) Malta’s Emerging Capital by the Sea. Accessed December 19, 2022.

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention Megalithic Temples of Malta. Accessed December 19, 2022.

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention City of Valletta. Accessed December 19, 2022.

- Valantinavicius, M. et al. (2020) Sheltering megalithic Temples in Malta—evaluating the process through data collection and modelling. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 949, 012035.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.