Voyageurs National Park

Downloads

- voyageurs_oli_2017286_lrg.jpg (2359x2045, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: October 13, 2017

- Visualization Date: October 6, 2022

It has been quite a journey through history for the land now called Voyageurs.

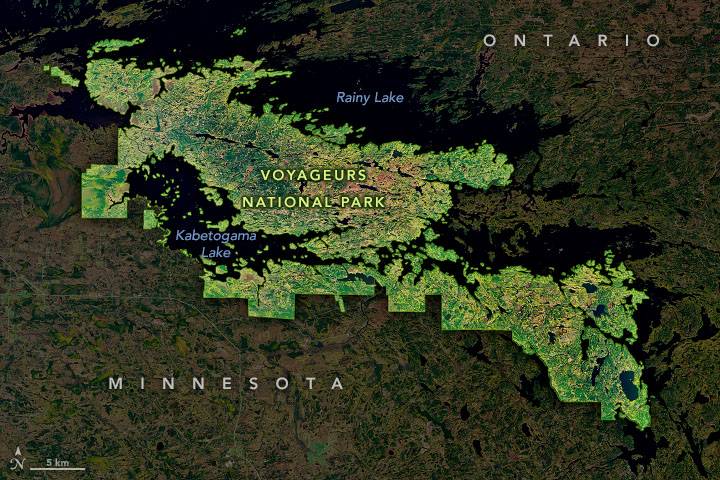

In northern Minnesota near the Canadian border, Voyageurs National Park spans nearly 350 square miles (910 square kilometers), though about one-third of it is water. The main landmass is Kabetogama Peninsula, which is sandwiched between Rainy Lake and Kabetogama Lake. The Canadian border bisects Rainy Lake.

Established in 1975, the park was named after French “travelers”—the fur traders who hunted and fished these waterways during the 18th century. However, there is evidence of humans coming and going through this area for at least 10,000 years. In the centuries since North America’s colonial era, the area has drawn waves of homesteaders, loggers, prospectors, and commercial fishers.

Today, most travelers to the area are seeking rest and recreation on the park’s numerous waterways, 500 islands, and more than 650 miles (1,000 kilometers) of shoreline. Many visitors venture through the park by houseboat, as all of the campsites are accessible only from the water for much of the year. In the icy winter, some sites can also be reached by foot or snowmobile. Hiking and ski trails allow access to the interior of Kabetogama Peninsula.

This image, acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 on October 13, 2017, shows fall foliage on the peninsula. This boundary ecosystem hosts both northern boreal species—like spruce, fir, aspen, and paper birch—and southern species—pines, oaks, maples, and basswood.

In autumn and winter, with lengthening hours of nighttime darkness, many park visitors come for views of the aurora borealis, or “northern lights.” The park offers low levels of light pollution year-round to those also seeking clear views of the night sky. In 2020, Voyageurs was designated an International Dark Sky Park.

Many smaller lakes dot the Kabetogama Peninsula and the smaller islands surrounding it; some of the islands have lakes that have islands of their own. This watery landscape is the result of glacial processes dating back thousands to millions of years and geologic processes going back billions.

The park sits on the Canadian Shield, the center of the North American craton, or geologically stable core of the continent. The rocks here began forming during the Archean Eon, more than 2.5 billion years ago. During the Pleistocene ice ages, from about 2.5 million to 12,000 years ago, ice sheets up to 3 kilometers (2 miles) thick spanned much of Canada and the northern United States. The massive load of ice depressed the crust. The advances and retreats of glaciers scoured the land, gouging out depressions that would become lakes and bogs each time the ice melted. The hard bedrock below the land surface allows little drainage; hence the extensive waterways seen today.

In the vast stretch of time between the eras of ancient bedrock and the massive glaciers, the area experienced episodes of mountain building, erosion, volcanism, and submergence beneath a shallow inland sea.

References

- International Dark-Sky Association (2020, December 7) Voyageurs National Park Certified as International Dark Sky Park. Accessed September 23, 2022.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2006, October 1) Voyageurs National Park.

- National Park Service (2022) Voyageurs National Park. Accessed September 23, 2022.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Sara E. Pratt.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.