Where Ice Still Flows into Glacier Bay

Downloads

- tarr_tm5_1986249_lrg.jpg (2711x1807, JPEG)

- tarr_oli_2019260_lrg.jpg (2711x1807, JPEG)

- glacier_bay_locator_lrg.jpg (6514x5022, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 5 - TM

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: September 5, 1986 - September 17, 2019

- Visualization Date: September 10, 2020

Today’s Image of the Day concludes a three-part series exploring the changing landscape in Glacier Bay National Park. Read about glaciers west of the bay here, and about the glaciers around the bay’s East Arm here.

In Glacier Bay National Park, the rugged landscape of water, ice, and life is in flux. Icebergs tumble from the fronts of glaciers, and plants are filling in where ice once covered the ground. Scientists and park staff have had a front row seat to all of the dynamic changes through the seasons and years.

“Seeing glaciers like Margerie, Lamplugh, Reid, and Grand Pacific is like seeing old friends,” said Emma Johnson, an education specialist at the park in southeastern Alaska. “I can recognize them immediately and tell how they have changed from week to week.”

The glaciers are all located in the West Arm of Glacier Bay, part of the Y-shaped inlet that is home to the majority of the park’s tidewater glaciers. Until the late 1980s, the park’s daily tour boat cruised up the bay’s East Arm for close-up views of tidewater glaciers—so-called because they flow directly into seawater. But the retreat of the East Arm glaciers onto land has sent tour boat operators into the West Arm instead, where a handful of impressive glaciers still touch the sea.

“The terminus of the tidewater glaciers is what most people see, but their stories are so much bigger,” Johnson said. “Satellite imagery was critical for helping me and other park rangers see the magnitude of change that has already happened in Glacier Bay.”

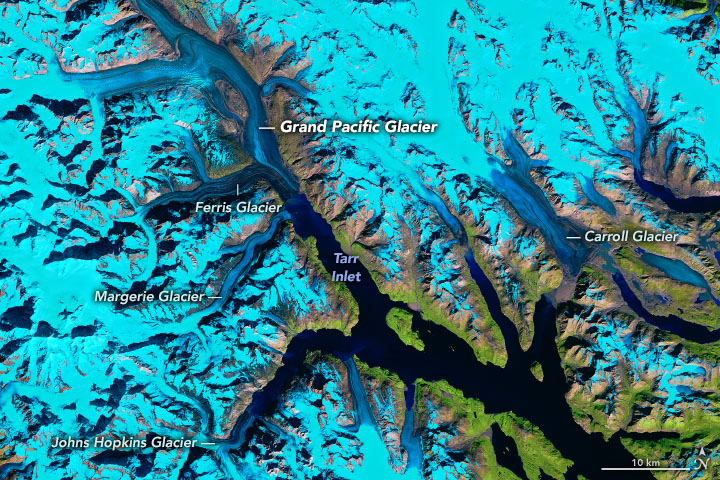

Several decades of change around the West Arm are visible in the images at the top of this page, acquired in September 1986 with Landsat 5 and September 2019 with Landsat 8. Snow and ice are blue in these false-color images, which blend infrared and visible wavelengths to better differentiate areas of ice, rock, and vegetation.

Johnson pointed out that the glaciers have changed in different ways over the years. Grand Pacific, for example, advanced into Tarr Inlet for several decades and even joined Margerie Glacier for a bit in the early 1990s before retreating again. Today the glacier is separated from Margerie and its front is completely covered in rocky debris. “More ice used to be visible on the face of Grand Pacific,” Johnson said. “Now I really have to tell people that it’s a glacier or they won’t recognize it.”

Margerie is the tidewater glacier that visitors see up close, floating within a quarter mile of its face to watch icebergs calve from the front. Other than the calving—a natural part of a tidewater glacier’s life cycle—the front of Margerie remained generally unchanged from the time Johnson arrived at the park in 2009 until about 2017.

“Margerie was the glacier we highlighted to tell our story as a park with stable or advancing glaciers in a world with overwhelming glacial melt,” Johnson said. In recent years, however, the glacier has pulled away from a small beach on the southern side, and bedrock is now exposed on its northern side.

Farther south in the bay, Johns Hopkins Glacier is the only tidewater glacier in the park that has been advancing in recent years. The park’s tour boat lets visitors view it from afar—about six miles away, at the entrance to the inlet. But Jason Amundson, a glaciologist at University of Alaska Southeast, has been getting a close-up view.

In summer 2019, Amundson and colleagues deployed cameras near the glacier front as part of a multi-year project to track iceberg motion. Icebergs in Johns Hopkins Inlet serve as important habitat for harbor seals, and scientists want to know how this constantly changing habitat is affected by processes such as iceberg calving, glacier runoff, and fjord circulation.

In a preliminary analysis of the photos, Amundson was surprised by the lack of icebergs calving in the fjord in 2019, likely due to the buildup of a moraine at the glacier’s end. Fewer icebergs would negatively affect seals that depend on the floating ice for habitat.

“The interesting story to me at Glacier Bay is how the shifting glacier landscape affects the rich marine ecosystem,” Amundson said. “Research into glacier-ecosystem interactions is pretty new, and so glaciologists and biologists are still learning how to talk the same language. The long history of research in Glacier Bay makes it an excellent place to study these interactions.”

References

- Landsat Science (2019, December 11) Watching Glacier Bay National Park Change. Accessed August 12, 2020.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2020, August 31) Inlet’s Iceberg Maker Is Nearly Gone.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2020, August 13) Grand Plateau Glacier.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2020, June 30) Johns Hopkins Glacier.

- National Park Service (2020, September) Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve. Accessed September 10, 2020.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), and land cover data from the Multi-Resolution Land Characteristics (MRLC) Consortium. Story by Kathryn Hansen, inspired by Landsat images prepared by Christopher Shuman (UMBC) for the Earth to Sky partnership between NASA and the National Park Service.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.