La Malinche’s Barrancas

Downloads

- lamalinche_oli_202009.jpg (720x480, JPEG)

- lamalinche_oli_202009_lrg.jpg (2291x2291, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: January 9, 2020

- Visualization Date: August 28, 2020

Today’s story is the answer to the Earth Observatory August puzzler.

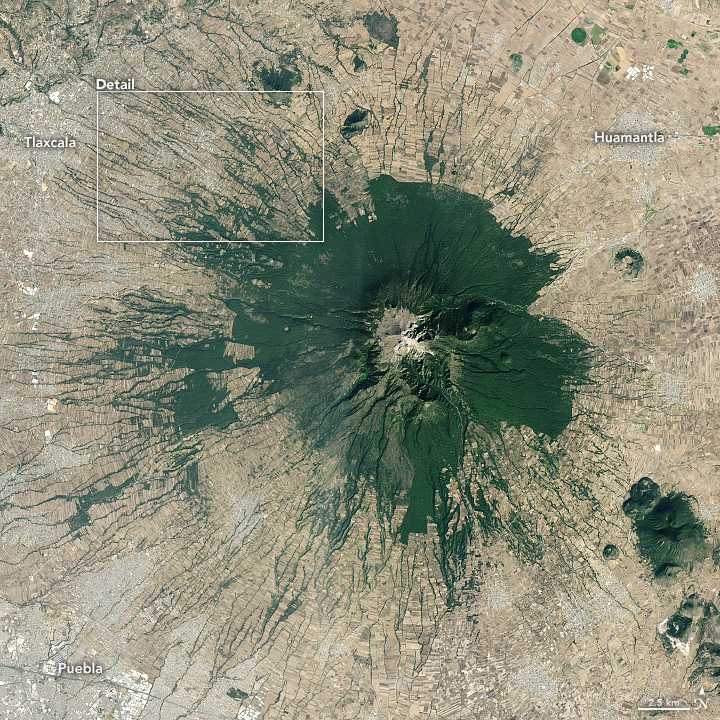

With an elevation of 4462 meters (14,639 feet), La Malinche volcano in central Mexico soars above the patchwork of cities, farms, and forests in the surrounding lowlands. Montane grasslands and shrubs dominate at the highest elevations, the heart of La Malinche National Park and the coolest part of the eroded, dormant volcano. At lower elevations, a ring of pine, oak, and alder forests covers the mountain’s middle slopes before transitioning into a tapestry of farmland, villages, and narrow stream valleys called barrancas.

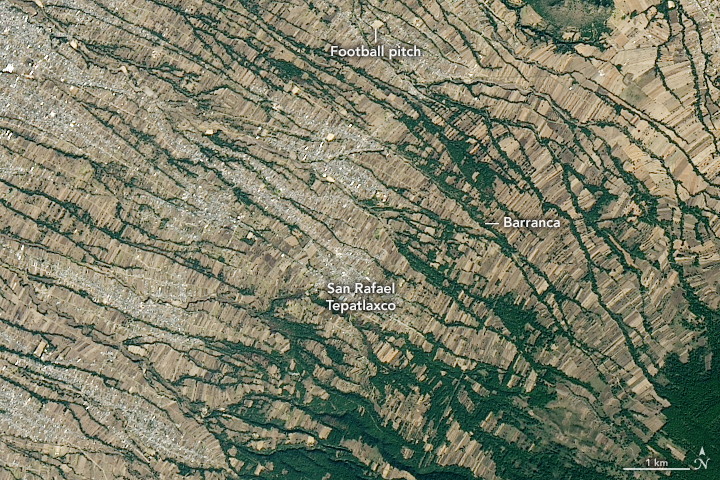

On January 9, 2020, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired a natural-color image of part of the northwestern side of the mountain, near the village of San Rafael Tepatlaxco. Several barrancas, many of them flanked by trees, cut across the sloped landscape. The image below offers a broader view of the whole mountain.

Since the barrancas are dry much of the time, maize farmers in the area do not rely on them for water and instead depend on rainfall. However, barrancas play a key role in the rural communities on La Malinche. During the dry season, they serve as channels for vehicle and foot traffic, convenient areas to set up football (soccer) pitches, and places to dredge for sand that can be used to make concrete or other building materials.

By local tradition, some local newlyweds even sift through the alluvium in the barranca bottoms to gather materials to make a few concrete blocks for their first home, Matthew Cole LaFevor explained as part of his University of Texas at Austin dissertation. The barrancas resemble a kind of “no man’s land or commons where community activities can take place—similar to the embanked floodplains of the batture lands along the Mississippi River that lay between the levees and the main channel, for which land tenure is often uncertain,” he wrote.

References

- Castro-Govea, R. & Siebe, C. (2007) Late Pleistocene-Holocene stratigraphy and radiocarbon dating of La Malinche volcano, Central Mexico. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 16 (1-2), 20-47.

- Franco-Ramos, O. et al. (2019) Reconstruction of debris-flow activity in a temperate mountain forest catchment of central Mexico. Journal of Mountain Science, 16 (9), 2096-2109.

- Global Volcanism Program La Malinche. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- LaVevor, M. C. (2014) Conservation engineering and agricultural terracing in Tlaxcala, Mexico. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2013, October 29) La Malinche Volcano. Accessed August 28, 2020.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.