Rare Filling of Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre

Downloads

- lakeeyre_tmo_2018135_lrg.jpg (2001x1623, JPEG)

- lakeeyre_tmo_2019135_lrg.jpg (2001x1623, JPEG)

- lakeeyre_oli_2019125_lrg.jpg (7116x7907, JPEG)

- lakeeyrezm_oli_2019125.jpg (720x600, JPEG)

Metadata

- Sensor(s):

- Terra - MODIS

- Landsat 8 - OLI

- Data Date: May 15, 2018 - May 15, 2019

- Visualization Date: May 17, 2019

Modern Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre is a salt-encrusted, mostly dry and barren playa that occupies Australia’s lowest natural point, which is 15 meters (49 feet) below sea level. But 100,000 years ago, the lake basin was filled with water and 10 times larger than today. Fed by several permanent rivers, the lake was surrounded by a lush, green landscape that hosted giant wombats, kangaroos, marsupial lions, and a menagerie of other animals. Many of these animals, and much of the lake has long since disappeared due to climatic changes. But Australians are now getting a taste of what the lake was once like.

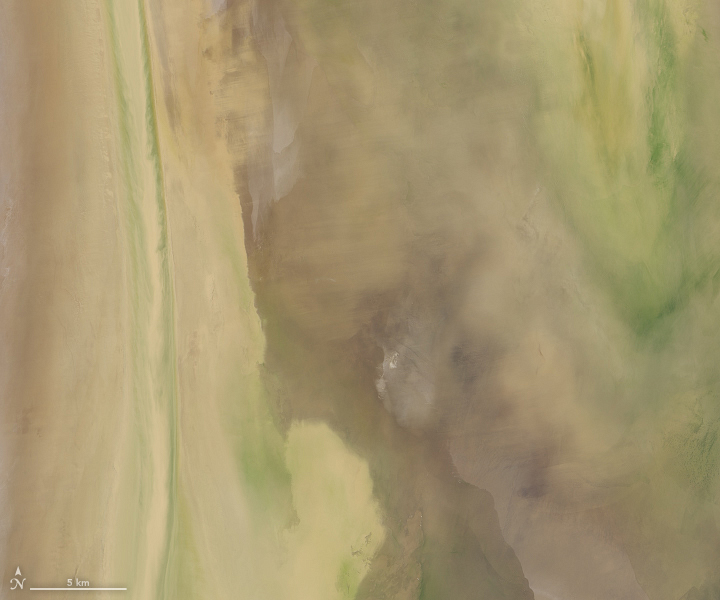

Storms dropped unusually abundant rain on northern Queensland early in summer and autumn 2019. Now that water has meandered through a long series of parched channels, watering holes, and lagoons and begun to fill the dried lake. Floodwater first began to flow into the lake in mid-March. When the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on Terra acquired this false-color image on May 15, 2019, the lake was nearly half full.

The false-color images were composed from a combination of infrared and visible light (MODIS bands 7-2-1). Water appears dark and light blue; bare ground is brown; and vegetation is bright green. This band combination makes it easier to see where water is present. Water first filled two narrow channels that run north to south; then it begun to pool in the southernmost part of Lake Eyre North. The natural-color images below, acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, provide a closer view of muddy water flowing into the lake on May 5, 2019.

Forecasters expect Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre to continue filling into June. Water will likely cover about three-quarters of the lake’s surface area toward the end of the month, putting the lake on track to reach its fullest state in more than 40 years. Typically, it fills completely only a few times per century; this most recently happened in 1974 and 1950. Smaller flows of water reach the lake every few years.

Between February and May 2019, more than seven Sydney Harbors worth of water have flowed into Lake Eyre, according to Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology. That is pretty fast, given that much of Lake Eyre basin is almost perfectly flat. In the past it has taken up to ten months for water to make the long journey from northern Queensland.

Wherever the floodwaters go, they have a transformative effect. Huge flocks of birds—including banded stilt—congregate at the water to feed on brine shrimp and lay eggs. Waves of fish, insects, and amphibians that are normally confined to watering holes have proliferated and spread widely. And blankets of green vegetation have emerged in places that were recently barren and brown.

References

- ABC (2019, May 15) Wild Abandon. Accessed May 23,2019.

- ABC (2019, May 11) Did you wonder what you were looking at? We explain those Lake Eyre shots. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Bureau of Meteorology (2019, May 20) Queensland floods: the water journey to Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Bureau of Meteorology (2019, May 20) Flows into Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre Autumn 2019. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Habeck-Fard, A. & Nanson, G. (2014) Environmental character and history of the Lake Eyre Basin, one seventh of the Australian continent. Earth-Science Reviews, 132, 39-66.

- Kingsford, R. (2017) Lake Eyre Basin Rivers: Environmental, Social and Economic Importance. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- The North West Star (2019, May 17) Lake Eyre Comes to Life. Accessed May 23, 2019.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Video by Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology with data from Himawari 8. Story by Adam Voiland.

This image record originally appeared on the Earth Observatory. Click here to view the full, original record.